cool neuroscience papers

Reading an array of papers and essays that are outside of my current electrophysiology/connectivity/modeling bubble definitely takes away the time that I could spend feeling guilty about my code not working, but it’s still pretty fun. Here are some very good pieces of writing on three particular topics I’ve been pondering lately.

Overpromising and overselling in science

“Promisomics and the Short-Circuiting of Mind” by Gomez-Marin, 2021 criticizes the popularity of “-omics” approaches to mapping the brain. These approaches focus on collecting unbelievably huge amounts of data in hopes that more data leads to more understanding: projects like the Blue Brain Cell Atlas used supercomputers to model millions of neurons and their connections. But more often than not, these maps ignore a lot of complexities - diagramming a circuit does not take into account individual variability or dynamical contributions of memory and experience, and, even worse, are built under a faulty assumption - that knowing where every node is and how it connects to others will magically reveal how the entire machine operates. “An infinite resolution map is not the territory”.

As someone who works with connectivity data, this is a challenging read, but I am inclined to agree with it, at least in part. Similar to the infamous “Could a Neuroscientist Understand a Microprocessor?” paper, the criticism of the approach is on the conceptual level - if we don’t know what process the circuit is implementing, it’s not helpful to know its wiring diagram (and the steps to take to remedy the situation are not very clear). The emphasis could be shifted from “more data, higher resolution” to developing high-level models that allow us to understand what data to gather and how to understand it best.

Talking about the unpleasant consequences of the scientific model as it is now, “From Scientists to Salesmen”, an article by Jennifer Lee highlights some of the worst current trends: increasing emphasis on self-promotion and marketing of your scientific “brand”, the profitability (both in money and scientific “clout”) of quick and flashy advances, competition between labs and the scramble for publications impeding genuine progress.

The author calls for increased collaboration within science, as well as the creation of positions that allow scientists to simply work without feeling the need to claw their way to the top while pushing out paper after paper. Academia is a precarious job, which doesn’t bode well for our quest of understanding “life, the universe and everything” - try doing that if you don’t know if you’ll have a position in 2 years.

Scientific revolutions and paradigms

“The Structure of Scientific Revolutions” by Thomas Kuhn has been gathering dust on my shelves for about 4 years, but hooray, the day has come for me to pick it up. According to Kuhn, science is not a slow incremental process, but rather waves of scientific paradigms disrupting each other (example: Copernicus and heliocentrism). Paradigms typically change when anomalies that can’t be accounted by current theories are discovered, but also when enough people agree to change them.

This book was sometimes criticized for reminding people that scientists aren’t paragons of objectivity and can occasionally be human with all the resulting irrationality. The balance between eroding people’s trust in science and instilling healthy skepticism can be pretty hard.

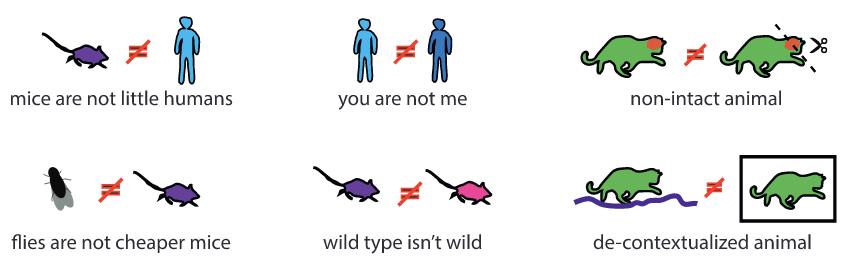

I want to hand this image out at conferences (Figure 2 from Gomez-Marin and Ghazanfar, 2021)

Some examples of suggested paradigm changes: in a scathing article directed primarily at other scientists, Gomez-Marin and Ghazanfar, 2021 write that “bodies aren’t just brain-holding vats that passively react to the environment”, “behavior isn’t just a stimulus-response operation” and “mice are not tiny humans”, single-handedly devastating the entire cognitive neuroscience community. I don’t think this massive paradigm change will be fully in effect any time soon, but one can hope.

Other fields have also been getting their fair share of criticism from the inside. Weiss and Shanteau, 2021 discuss the current reigning paradigm in decision making research and how it led to seemingly fruitful research with little to no connection to how people actually make decisions “in the wild”.

Design and visualization

This is a much less heavy topic than “oof, science can be bad”, but is probably equally important. Awkward, cramped and hard to understand visualizations are the bread-and-butter of science, but it doesn’t have to be this way. The importance of good design also borders more serious issues, such as inaccessibility of scientific findings to laypeople and bad science journalism.

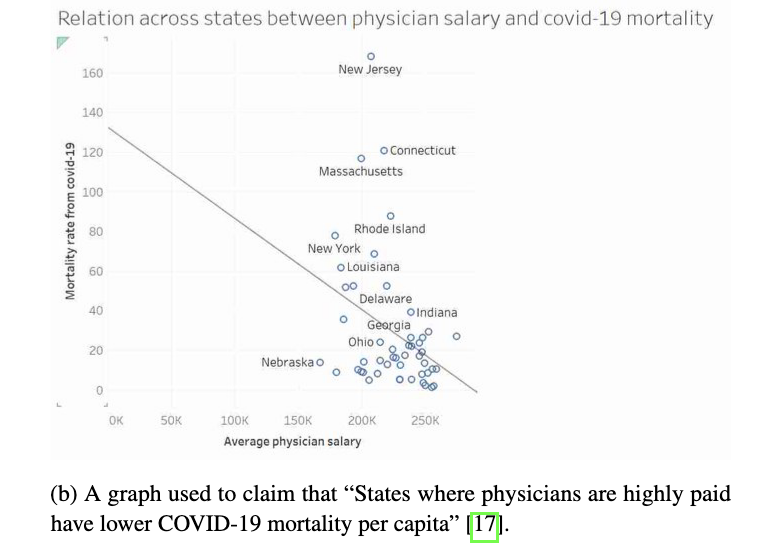

Color me convinced! (Figure from Corell, 2021)

Corell, 2021 discusses “bullshit visualizations” that, intentionally or not, muddle, obscure or straight up change the message of the data. These types of visualizations are less prominent in science, but it’s still a good reminder to not use more visualizations than you have to and make sure you are not deceiving anyone.

Crameri et al, 2020 talk about how colormaps can mislead the interpretation of data (TL;DR: don’t use the rainbow colormap, it’s bad!). I wish there was more concrete and easy to use advice out there on visualizations: every time I have to make a figure, I realize that I don’t know anything about colors or how to combine them effectively. If you know any good resources (as long as they don’t insist on telling me that red is a color that indicates passion), let me know.